Deep-sea mining is emerging as a highly polarising topic, hailed by its proponents as a breakthrough for the global green energy shift, while opponents warn of its potentially irreversible environmental consequences. Though not yet operational at a commercial scale, that may soon change as Canada’s The Metals Company moves ahead with plans to mine in the Pacific.

What is deep-sea mining targeting?

Three main types of mineral-rich deposits can be found on the ocean floor:

Polymetallic nodules: These are small, round mineral lumps that form over millions of years from particles such as fish bones or shark teeth. Found 4,000–6,000 metres deep, especially in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawaii and Mexico, they contain high concentrations of manganese, cobalt, copper, nickel, and iron.

Cobalt crusts: These rocky layers form at depths between 400 and 4,000 metres by accumulating metals from seawater. Found mainly in the northwestern Pacific, they are rich in manganese, cobalt, iron, and platinum but are difficult to separate from the seabed.

Sulfide deposits: These are located near underwater volcanic vents at depths of 800 to 5,000 metres in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. They contain valuable metals like copper, zinc, silver, and gold.

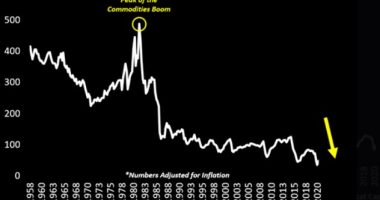

Why the interest in mining them?

Many of the metals found in these seabed deposits—especially cobalt and nickel—are crucial for producing batteries used in electric vehicles, a cornerstone of the transition to clean energy. Copper, too, is in rising demand for electric infrastructure. Supporters argue that harvesting nodules is less environmentally invasive than traditional mining, which often involves large-scale land degradation and toxic chemical processing.

What are the environmental concerns?

Despite the mineral riches, the deep sea remains one of the least explored and most fragile ecosystems on Earth. Its role in carbon storage and overall ecological balance is not yet fully understood.

Environmental groups and scientists worry that mining could severely damage these ecosystems, destroying unknown species and habitats, altering chemical balances in ocean waters, and introducing pollution through noise, light, and potential equipment leaks. Greenpeace and other conservation groups warn that the damage could be long-lasting or irreversible.

To date, 32 countries—including Canada, Germany, the UK, Brazil, and Mexico—have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining in international waters, pending further research.

What is the current status of deep-sea mining?

Commercial mining has not yet begun anywhere in the world, although several nations have initiated exploratory projects in their exclusive economic zones.

The most advanced mining technology is currently designed to collect polymetallic nodules. Japan and the Cook Islands are already conducting exploration, with the latter also working alongside China. Europe’s Norway had initially planned to begin issuing licences in 2025, but this has been pushed back to 2026 due to political disagreements.

In international waters, oversight is handled by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which has issued exploration licences but is yet to finalise a legal framework—dubbed the “mining code”—for actual exploitation. The code has been under negotiation since 2014.

Frustrated by the delays, The Metals Company has applied directly for a mining licence within US jurisdiction in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, bypassing the ISA entirely. This move was made possible under a 2020 executive order by former President Donald Trump that allows US-based firms to pursue deep-sea mining even outside national waters.